Smalltalk > Motivation

What was the goal of Smalltalk, and what motivation led to it being created?

Smalltalk could be said to have been motivated by two goals: a narrower goal of teaching programming, and a broader goal of supporting the creative spirit.

Teaching Programming

Buck and Latta summarize Smalltalk as follows:

Smalltalk is an object-oriented programming language, and it was developed back in the early 1970s at Xerox PARC in California. It was a team called the Learning Research Group at Xerox, and they built it mostly to teach kids how to program computers.”

(SR2 2:00)

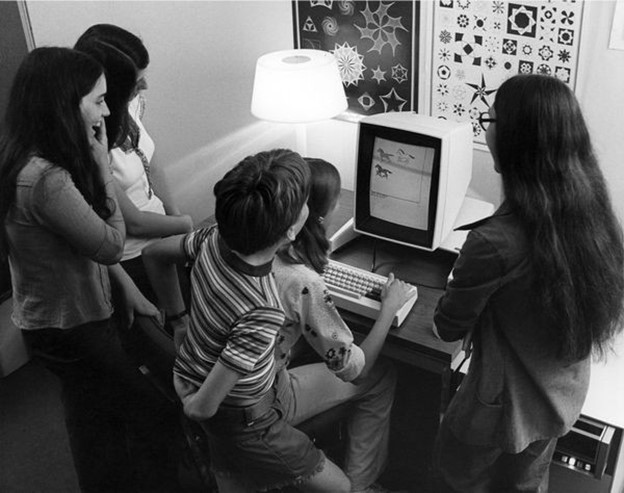

To add a bit more detail to this, it must be remembered that computers at this time were quite large and expensive, but PARC had a vision of computers that were quite a bit different:

Guided by Alan Kay’s vision, Dan Ingalls along with Ted Kaehler, Adele Goldberg, Larry Tesler, and other members of the PARC Learning Research Group created Smalltalk as the software for the Dynabook, their aspirational model of a personal computer.

(WB)

In describing the later launch of Squeak, Ingalls explicitly draws a parallel between their intent there and the original intent of Smalltalk:

As exciting as the day the interpreter first ran, was the day we released Squeak to the Internet community. In the back of our minds, we all felt that we were finally doing, in September of 1996, what we had failed to do in 1980.

(Squeak)

What was it they had failed (but intended) to do in 1980? Ingalls writes:

In December of 1995, the authors found themselves wanting a development environment in which to build educational software that could be used—and even programmed—by non-technical people, and by children.

So the goal of allowing children to program is reaffirmed, along with non-technical people.

The Creative Spirit

“Design Principles Behind Smalltalk” gives a broader picture of the viewpoint that led to Smalltalk. The first line summarizes it:

The purpose of the Smalltalk project is to provide computer support for the creative spirit in everyone.

(Design)

How does Smalltalk uniquely support “the creative spirit in everyone?”

Personal Mastery: If a system is to serve the creative spirit, it must be entirely comprehensible to a single individual. The point here is that the human potential manifests itself in individuals. To realize this potential, we must provide a medium that can be mastered by a single individual. Any barrier that exists between the user and some part of the system will eventually be a barrier to creative expression. Any part of the system that cannot be changed or that is not sufficiently general is a likely source of impediment.

Single individuals are empowered to access all parts of the system because it is written in a single language, Smalltalk, all the way down as much as possible. Also, Smalltalk is set up so that any part of it can be changed in the same development environment. More concretely:

a researcher, professor, or motivated student can examine source code for every part of the system, including graphics primitives and the virtual machine itself, and make changes immediately and without needing to see or deal with any language other than Smalltalk.

Next, Smalltalk is intended to work with the way the human mind has evolved to work, not to work against it:

The mechanisms of human thought and communication have been engineered for millions of years, and we should respect them as being of sound design. Moreover, since we must work with this design for the next million years, it will save time if we make our computer models compatible with the mind, rather that the other way around.

What is this design that works with the mind? Objects.

HomeWe have said that a computer system should provide models that are compatible with those in the mind. Therefore: Objects: A computer language should support the concept of “object” and provide a uniform means for referring to the objects in its universe.