HyperCard > Properties

What defining characteristics influence how HyperCard uniquely works?

Interactive Document

Bill Atkinson realized that what was needed to allow non-programmers to create software was a kind of interactive document:

Now, I’d just come from a world where we pasted a tennis shoe into a MacWrite document, and now the world dealt with words and pictures. And I thought, really what you want is also interaction: you want to express something in a way that someone can interact with what you’ve made. An interactive document.

(TWiT 26:22)

An interactive document would exist in the space between a typical document and an application:

So what HyperCard is attempting to do here is to offer a new media that’s between the application on the one hand and the document on the other.

In Macintosh, a document contains information. It’s made by a user and that information is relatively passive: it’s acted upon by the application over here. The application has lots of interaction in it; usually not very much information. And the application can only be made by a programmer.

What HyperCard offers is a new format in between–the stackware format–that has information like a document and has interaction like an application program. And yet it’s simple enough that users can put them together using an approach that I call ‘the software erector set.’

(BAPH 4:44)

But what exactly would an interactive document be like? The metaphor Atkinson hit upon was a stack of cards:

So I said, let’s make a stack of cards and each card can have graphics on it, and text on it, and buttons that you can touch and they’ll do something: they’ll go to another card, or another card in another stack. And maybe they’ll make a video go to a certain frame. There needed to be some flexibility about what the buttons did.

(TWiT 26:42)

Simple Tools

Atkinson’s focus on what functionality to put into HyperCard was a simple complete set:

…how do I choose what would be in and not…it was about what was needed in order to make a complete kit. You can’t get an erector set that doesn’t have any round things; it’s not going to work. But there is a certain set of things that does make a complete and usable kit. And that’s what I was always looking for, is the cleanest, simplest set of tools that would empower a lot of different things.

(Legacy 42:50)

This simple set boiled down to mostly graphics, text, and buttons:

The combination of graphics and text and buttons seems to be a relatively simple format that can express a fairly wide variety of different kinds of interactive information.

(BAPH 40:30)

There was an intentional decision to exclude more specialized functionality, such as reporting:

…reporting on portions of a stack. I know of several vendors who are putting together report-generation programs [to extend HyperCard] that do much fancier reporting than is in HyperCard. I didn’t really want HyperCard to turn into this big grandiose database with 50 zillion things you’d have to learn about report generation.

(BAPH 1:19:05)

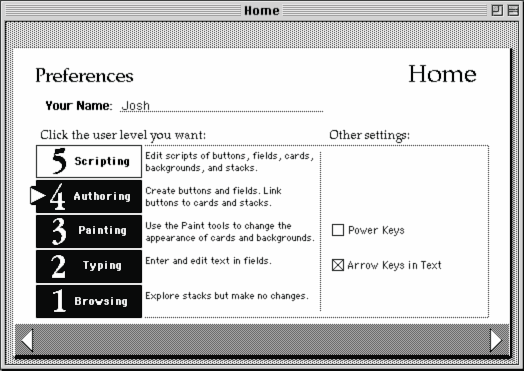

User Level

A key aspect of HyperCard’s design is the concept of user levels. As a user, you choose the level of functionality you want to operate at. The levels are:

- Browsing

- Typing

- Painting

- Authoring

- Scripting

- Programming (not pictured)

Here’s an introduction from Atkinson to most of the levels:

- Typing: “[HyperCard] initially comes at ‘typing’, which is one of the lower levels. This is enough to use all of the stacks that come with HyperCard; it’s enough to add cards to the address book and type in appointments and things like that. But there’s a growth path here that you can go further than that. At the typing level, the menus are relatively simple.” (BAPH 15:48)

- Painting: “If you decide to go the next level, painting brings up another menu that has in it painting tools.” (BAPH 18:41)

- Authoring: “The next level is an authoring level that, when you choose that, brings up yet another menu. The objects menu lets you start to see a little of the anatomy of a stack. You can see that it consists of buttons, fields, cards, backgrounds, and the stack itself. You can get information about those. And choosing the authoring level enables the button and field tools.” (BAPH 21:03)

- Scripting: “Another problem happens in the erector set, which is that they never had the piece that you want: you want a particular shaped piece, and they don’t have it, and they never have had it, and you don’t have a sheet metal stamp, so you can’t add to it. And that’s where HyperCard’s button library, that would be the same thing as if you went to the button library and they don’t have a button that does this, and there’s one that does similar to it, but not quite it. You can then modify it. That’s what the next user level is all about: scripting lets you see behind the buttons and modify and enhance them. And it’s okay if only a fraction of the HyperCard users learn the scripting language, because they’ll make a nice library of buttons for other people to cut and paste. My experience has been a lot of people are learning the scripting language.” (BAPH 32:51)

- Programming: “Now the last user level isn’t shown. It’s sort of off the end here, and it’s called programming. This programming level means you go and you buy a compiler and you learn how to write C or Pascal or assembly language and you learn how to call the Macintosh Toolkit interface, and a couple years later you’re ready to write a little piece of program that can then be called from the scripting language as though it were built in. It’s very easy, just as we can extend the button library by writing scripts, we can extend the scripting language by native code. So if you write a little ten-line Pascal procedure that puts out some bytes to the serial port to control, say, a video disc, then you can call that from within a script. And people can cut and paste buttons that use that without knowing about the programming side of it on the backend. In this way, HyperCard can- really, behind a button, you can have it do almost anything that the Macintosh can do.” (BAPH 38:36)

The levels function as a “growth path”:

If and when you decide to go beyond the typing level- …I think there are a lot of people who will be using HyperCard as an access tool to get at stacks that other people have made, and there’s a gentle gradual path to allow those people to become authors of information as opposed to just users, but it’s okay to stay a user of information. Think how many Walkmen Sony sells, and they don’t record. HyperCard is both a playback tool and an authoring tool.

(BAPH 18:01)

The levels are made to build on one another. For example, at the Authoring level, before you reach Scripting, you can already work with interactive functionality by moving around buttons with the scripts that come with them:

Now, the beauty of this is that when I pasted that button, I didn’t get just a picture of a button: I got its intelligence to come with it. That’s half of the beauty of the erector set approach, is that you’re actually moving around capability…So this is sort of how the software erector set approach works at making interactive information. You copy and paste or modify and paint yourself images until it looks the way you want it. And you copy and paste buttons until it acts the way you want it.

(BAPH 31:46)

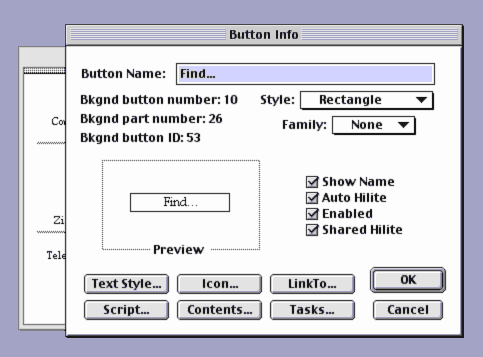

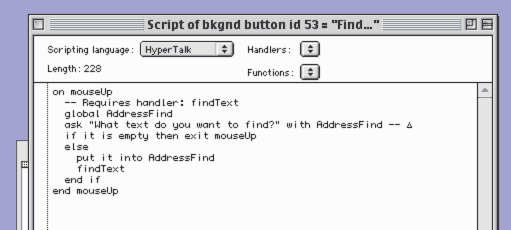

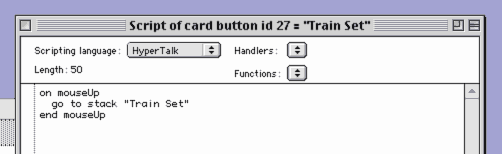

At the Authoring level you can hook up basic interactivity like setting a button to navigate to a certain card. When you do this, that functionality is implemented as an automatically-generated script. As a result, when you move to the Scripting level, you can see the script that was generated, learn, and modify it:

If we look at the button that was made when we said ‘Link To’, we can open up that. Now, we just chose “Link To’ from the dialog, but it wrote a little script for us that said ‘on mouseup go to card such-and-so’, go to a particular card. We could modify this script…

(BAPH 36:50)

One effect of the user level approach is to aid gradual learning:

a lot of people are using it not at the scripting level and are not being thrown the full complexity at the beginning. And it’s okay, you can set yourself in scripting level and have all the stuff available at once, but beginners really have an easier time- their first one hour is really much better at the typing level because they can use all the stuff without having to get into scripting right away.

(BAPH 1:14:33)

And in fact the more visual early levels can be a bridge to the more theoretical programming concepts:

So this is how you make these thematic threads through information. You say ‘well, if he clicks here I want him to go there; if he clicks here I want him to go there.’ And for a lot of people this is the beginning of branching control in a program. A lot of people who are afraid of the if/then/else construct…find it comfortable to use the linking concept here…it’s a lot less foreign to most people than programming constructs

(BAPH 24:15)

High-Level Language

When you do get to scripting, the programming language you use is called HyperTalk. This language functions at a much higher level than its contemporaries:

One of the big differences between this programming language and things like Pascal or C is that the concepts here are much, much higher level. You’re dealing with the logical entities that you’re interacting with, rather than- well, like, Pascal doesn’t even know what a rectangle is. The object level at most programming languages is too general to be useful for a specific environment.

(BAPH 42:36)

One of the motivations for the high level of HyperTalk was to make the learning path for users easier:

The primary requirement of the HyperTalk language was that it be readable by somebody that can look and see what was going on: “oh, on mouseup go to next card”. Somebody could see that, and maybe modify it a little bit.

(Legacy 6:51)

Use, Then Reuse, Then Tweak, Then Create From Scratch

HyperCard stacks are open source in the sense that you can see the source, not only by downloading it separately, but right in the middle of running the program:

I was open source before open source was cool. You could open any button up, and see inside “on mouseup go card 3”. See how it worked, so that you could modify it for your own use. And a lot of people made HyperCard stacks by starting with somebody else’s and modifying it.

(TWiT 36:05)

Every HyperCard stack that you got had buttons and things in it, and people learned from each other, and it was kind of like an open source programming environment because people exchanged HyperCard stacks.

(Legacy 7:07)

The result was that you could progress from using provided stacks as-is, to customizing them, to creating something new from scratch:

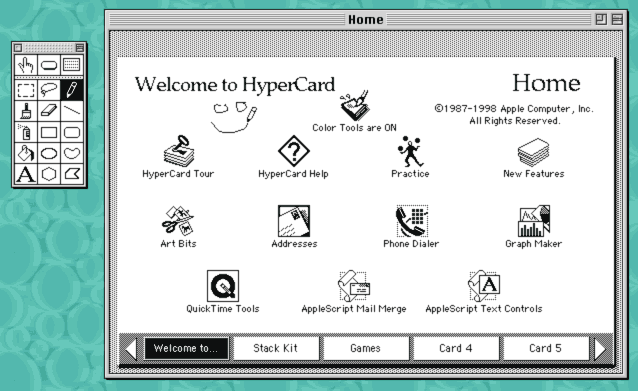

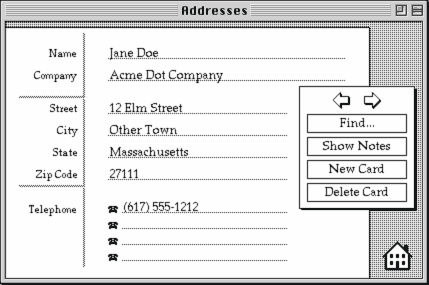

Now when you get HyperCard, it comes with these stacks here and the ones across the top are kind of a brochure showing the kinds of things you can build with HyperCard. These aren’t the end-all-be-all address book, and the world’s perfect calendar. Lots of people will want, say, a daily calendar instead of a weekly, or lots of different variations.

What they’re there for is a little bit like when you buy an erector set, it comes with boxes of parts, and it also comes with a brochure showing things built with that erector set. Like, for example, there’ll be a picture of a bridge and a picture of a car. And you’ll start first by building the things that are in the brochure, you’ll start by building the bridge, and you play with it a bit, use it. And then after a while you’ll want to customize it–you’ll make a longer bridge, or one with, I dunno, prettier spans, or something like that. And in the process of doing that small customization, you’re really learning how the whole thing works, how do the nuts and bolts and girders bolt together to make this thing. Later, what you’ve learned from that, you use to build a brand new object that wasn’t in the catalog, that wasn’t in the brochure–maybe you build a space ship.

The same kind of thing happens here in the software erector set. You’ve got a row here of stacks that are parts kits, and a bunch of example stacks that are a brochure of things you could build. These are actually already working ones, so you don’t have to build them right away, you can go ahead and use them right away. But after you’ve been using them, it’s very easy to customize them in small ways. You start by “oh, I wish this field had room for phone numbers.” Well, you choose the field tool, and you stretch it out a little bit. And a lot of times I’ve found software that I’ve run into has been frustrating in that, “oh, if they only had this a little different, it would be just right for me.” And there’s no way to make it perfect for everyone, unless it’s adjustable to individual people. And that’s what you start out with here, is adjusting or modifying the stacks that come with HyperCard, as teaching examples, and they’re quite useful as they come, but they’re also your teaching examples that bring you into creating your own fresh stacks.

(BAPH 25:12)

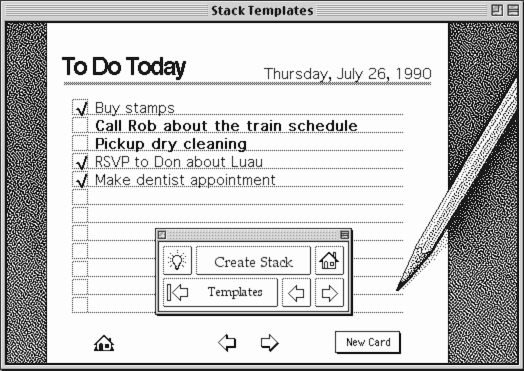

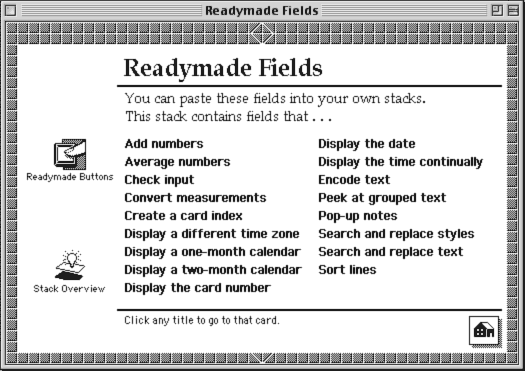

Beyond working example stacks, there are also non-working stack ideas:

Here’s a stack of stack ideas. Each of these is a little seedling for a new stack, a little template if you will.

(BAPH 28:20)

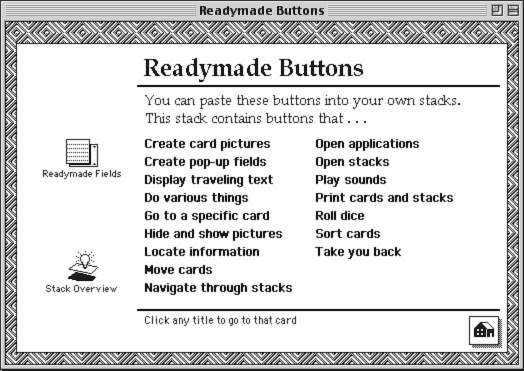

There are also parts kits that have standalone parts:

Each of the little parts kits that comes with HyperCard, they’re deliberately extensible–you can add your own card ideas, your own stack ideas, your own art ideas, your own button ideas, to them.

(BAPH 30:45)

And in fact every stack functions as a parts kit:

Whenever you get a stack from somebody else it’s a new parts kit. There are buttons in it that you may want to learn from or copy and paste, there are sounds in it you may want to learn from; you may want to copy and paste them. Or graphics. A lot of the stacks people are releasing deliberately public domain for other people to build on top of. There’s a lot of sharing going on in HyperCard.

(BAPH 56:02)

Teaching By Example, Editability

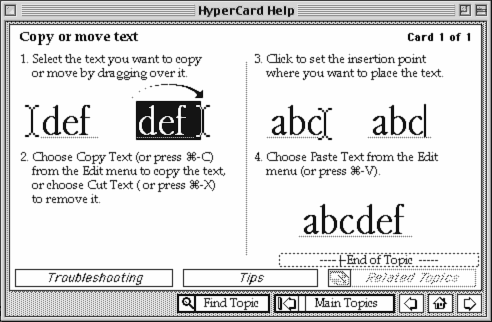

As a result of the openness of HyperCard, even the explicit teaching content is interactive and hackable as well:

Now there’s a help system that comes with HyperCard that is itself a HyperCard stack, and it teaches the features of HyperCard-all the things that you can do, and all of the language features, and things like that. It also teaches in another way, by example. This is an example of using HyperCard for training information. You can learn by dissecting this stack, as well as by using it.

(BAPH 39:49)

In The Box

One crucial aspect of HyperCard’s impact isn’t in the software itself but in how it was distributed. After it was released, it was included “in the box with every Mac”. Atkinson considered this to be necessary:

It was an exchange medium…You want people to be sharing stuff. They all have to have the software that it takes at least to play it, but hopefully to be able to author it also. So I worked out an arrangement with Apple that it would be bundled free, be in the box with every Mac…

(Legacy 10:37)

What made HyperCard the ubiquitous product it was in the early 90’s as opposed to the niche product SuperCard and Revolution [successors to HyperCard] are today was the fact that it was included free with every Macintosh sold. So anybody could use it to create something, then share their creation with somebody else with the confidence that the other person would be able to run it.

(xTalk, Bettencourt)

Automatic Persistence

One aspect of HyperCard that is easy to miss is that persistence was automatic. The setup of the stack, text entry, and even which card you were on was automatically saved. Atkinson says:

[Users] didn’t have to worry about saving the field out to the disk and all that–I take care of that. There were high-level things, automatically retained information, you put something into a field and it’s there, and if you unplug the computer it’s still there. In fact, that was one of my goals, I didn’t like the way you had to save documents. So my idea was, if you have done something, and you unplug the computer from the wall, it has to have everything we’ve done up to within a few seconds. So it always was trickling stuff out…Having to save a document was a mistake.

(TWiT 26:20)

Home