HyperCard > Competitors and Successors

What other products emerged to compete with HyperCard and/or carry on its legacy? This is a complex question because HyperCard was used for so many different things. Oren writes:

What was this thing? Programming and user interface design tool? Lightweight database and hypertext document management system? Multimedia authoring environment? Apple never answered that question. Probably the answer was “yes, all of the above”, and HyperCard could have been forked into several related products, each tailored to a specific market.

I would argue that this breadth wasn’t due to overreach; it was due to the size of the gap that HyperCard filled. The needs it met included:

- Making it easier and cheaper for people to learn to program

- Allowing people to organize their own data

- Allowing people to share information with others

- Allowing people to customize their software

- Allowing people to create interactive experiences

DeVoto describes HyperCard successors in this way:

All of the [HyperCard] clones concentrate on certain aspects of HyperCard that their creators found most important: professional power in an xTalk, easy interface building, appeal to novices, appeal to “do it yourselfers” (not necessarily the same group as novices!), etc. So there is a broad spectrum, but no single product that’s targeted exactly the same way HyperCard was, although you can pick any aspect and point to a clone that maximizes that aspect.

(xTalk, DeVoto)

As HyperCard illustrated what could be done in these areas, gradually other specialized tools cropped up. Whether intentionally or not, they chipped away at the area that HyperCard added value. They include:

Learning to Program

Freedman describes how HyperCard filled a need for entry-level programming that has since partially been filled by other languages:

“Back then, you needed to learn a low-level programming language (C/C++/Pascal) if you wanted to create something for your Mac. You needed to be a “professional” programmer. HyperCard finally provided entry-level and hobbyist programmers with an option. Things are very different today, however. Hobbyists now have so many options: Ruby, Python, RealBasic, Flash, JavaScript, etc. While I am still not convinced that they are as easy to use as HyperCard was back then, they have rendered a new HyperCard less necessary…many of them still feel more like “programmer tools” than consumer products. So in that sense, we still need something that fills at least some of the unclaimed roles left behind by HyperCard.”

(xTalk, Freedman)

Back when HyperCard was introduced, Atkinson pointed out in a tongue-in-cheek way the contrast between the ease of HyperTalk and the difficulty of other contemporary languages:

This programming level means you go and you buy a compiler and you learn how to write C or Pascal or assembly language and you learn how to call the Macintosh Toolkit interface, and a couple years later you’re ready to write a little piece of program that can then be called from the scripting language as though it were built in. It’s very easy, just as we can extend the button library by writing scripts, we can extend the scripting language by native code.

(BAPH 38:46)

So Atkinson sees a role for programmers and set up HyperCard to allow it to be extended, but at the same time he wants to emphasize just how high-effort it is to create software in that way. In HyperCard it is only the most specialized places that that kind of programming is used, and elsewhere you can use a much higher-level language.

Organizing Data

FileMaker (which predates HyperCard) and Microsoft Access (which was released in 1992) are two examples of personal data systems that focus on tracking and working with data and de-emphasize creating interactive experiences. As the functionality of such systems has expanded, the need for a system like HyperCard for organizing data has decreased.

Sharing Information

HyperCard allowed people to share information with one another by sending each other stacks, and the web took that ability and supercharged it by providing instantaneous access to pages over the internet.

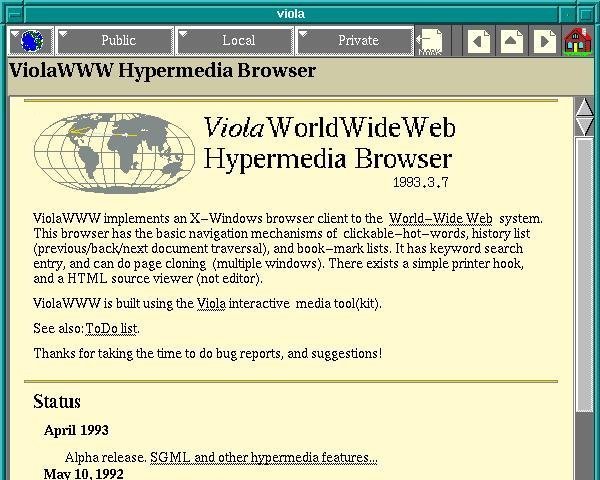

But the relationship between HyperCard and the web goes deeper than just the use case of sharing information. The interface of the web browser itself was inspired by HyperCard. This included ViolaWWW, an early experimental browser:

Berners-Lee created his own World Wide Web browser, then released the coding library for the project so that programmers could develop their own versions…These included Pei-Yuan Wei, working on UNIX X-terminals at UC Berkeley’s Experimental Computing Facility. Where did Wei derive inspiration for his “ViolaWWW” web browser? He took his lead from a program that he found fascinating, even though he did not have a Mac of his own. “HyperCard was very compelling back then, you know graphically, this hyperlink thing,” Wei later recalled. “I got a HyperCard manual and looked at it and just basically took the concepts and implemented them in X-windows,” which is a visual component of UNIX. The resulting browser, Viola, included HyperCard-like components: bookmarks, a history feature, tables, graphics.

(Ars)

Mosaic, the browser that eventually developed into Netscape Navigator, was also influenced by HyperCard:

Mosaic came out six years after HyperCard, although it didn’t copy any of the code. Marc Andreessen wrote me a sweet little note saying “thank you for the inspiration,” just for the ideas. So, the web was, instead of a stack of cards, it was just pages. And pages had graphics on it, and text on it, and buttons that could take to someplace else.

(TWiT 28:15)

Atkinson contrasts HyperCard’s model with the web:

The web wasn’t there. And I sort of see in retrospect looking back that HyperCard was kind of like the first glimmer of a web browser, but chained to a hard drive. You got stacks of cards, it’s like pages on the web. You can put text and graphics on ‘em, and you can put links that take you to some other place. But because there wasn’t really widespread use of the web yet, it was kind of limited there.

(Legacy 5:09)

Atkinson also acknowledges that HyperCard could have played a more direct role in the web:

I missed the mark with HyperCard. I grew up in a box-centric culture at Apple. If I’d grown up in a network-centric culture, like Sun, HyperCard might have been the first Web browser. My blind spot at Apple prevented me from making HyperCard the first Web browser.

(Ars)

But he sees the impact:

And I feel that maybe the biggest impact HyperCard has had is actually not on the HyperCard stacks that people made but how it’s shifted people’s lives and how it’s influenced the development of further things, like the designers of Mosaic said that HyperCard was a great inspiration to them. And so I think the biggest expression of the success of HyperCard really is in how we now have this whole World Wide Web.

(Legacy 5:48)

But the web has at least one difference from HyperCard:

There was a little difference that HyperCard was always an authoring environment, never just a browser. I didn’t separate the guys who consume the information from the guys who create it.

(Legacy 6:25)

Here Atkinson calls the lack of an authoring environment on the web “a little difference”, but elsewhere we’ve seen just how essential he considered the authoring aspect to be.

This lack of authoring was eventually somewhat mitigated by blogs and wikis, which allow creating web content using the same tooling it is viewed with: the browser. The difference is that this content is non-interactive, a static document. If you want to create interactive software, you need different tooling. Web-based software development environments like CodeSandbox, Glitch, and replit are starting to bridge this gap. But while they remove the complexity of setting up local development environments, they still require developers to work through complicated development tooling and workflows to create software, far more complex than HyperCard was.

Customizing Software

Open source software allows some limited degree of customizing software, but there are a number of challenges: usually additional tooling needs to be installed to run the modified software beyond what is needed to run it, and lots of software is written with languages and APIs that require a person to be an experienced developer to modify them.

Creating Interactive Experiences

I would argue that it is far harder for non-programmers to create interactive experiences now. We create static content, not interactive content. Our industry is stuck in 1984 in MacWrite; we haven’t made the jump to 1987 to HyperCard.

Vano writes:

“Normal ten year olds can work with HyperCard, and that’s something I don’t think I can honestly say about any other system out there.”

(xTalk, Vano)

A guest at “The Legacy of Apple HyperCard” says:

There are a lot of people that wish HyperCard was still running. I used to teach it in 1990; I taught a class called “Designing Computer-Based Learning Environments,” which I couldn’t teach now because there is no environment or platform where I could take undergraduates with no computer experience, no programming experience at all, and bring them in and let them design things that they were passionate about teaching.

(Legacy 46:44)

She gives an example:

My favorite stack that someone designed was a credentialed student, and he wanted to make a stack that would help new teachers understand how to do classroom management. He didn’t make a tutorial, what he made was a simulation, which said “you’re at the front of the class, a student in the back starts throwing his pencil, what do you do?” And then gave a tree. So it was kind of an adventure game for classroom management. And it was the best way I think to understand good and bad decisions in classroom management that I’ve ever seen. And the format, the platform of being able to make a decision and see–obviously, that’s simulations, make a decision and see the outcome. But there’s no way that I could have a student now design something like that easily without a much steeper learning curve.

(Legacy 47:14)

Are there really no options for creating interactive content? In 2016 Atkinson himself describes iBooks Author as a successor:

You know where HyperCard is now? Really, in iBook Author [sic]. iBooks Author you can drag-and-drop premade modules that play videos, premade modules that do a stack of JPEGs. It’s really an authoring environment for the non-programmer to drag and drop, and just replace “stack of cards” with “book of pages” and you’ve got the same–but it’s much more powerful, and it’s color and has animations…and it has something in it that HyperCard never really had, which is a publishing arm. You write something in iBooks Author, and you say publish: it’s in the iTunes Store! Whereas HyperCard stacks, people had to put them on a sharing site…

(TWiT 35:05)

However, in 2020 Apple discontinued iBooks Author and recommended as a replacement Pages, a standard word processor with limited options for interactivity.

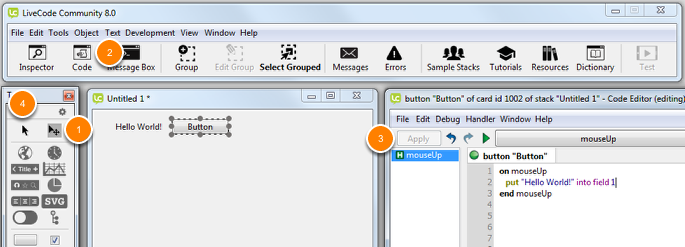

There have been a number of fairly direct successors to HyperCard, including SuperCard, MetaCard, Runtime Revolution, and currently LiveCode. Atkinson describes how close the last is:

LiveCode is probably the most complete sort of HyperCard-on-steroids. It’s a lot more, it’s not just HyperCard…It’s not as easy and approachable as HyperCard was, you can’t just walk up to it and have a casual relationship. You kinda have to dedicate a little time into learning how to use the system”

(Legacy 1:02:41)

A quote by Bettencourt about the limitations of earlier tools applies to LiveCode as well:

I still believe there is a need for an open-source HyperCard clone. SuperCard and Revolution are all well and good, but in my opinion they have two major problems: they’re expensive, and they’re proprietary. What made HyperCard the ubiquitous product it was in the early 90’s as opposed to the niche product SuperCard and Revolution are today was the fact that it was included free with every Macintosh sold. So anybody could use it to create something, then share their creation with somebody else with the confidence that the other person would be able to run it. That isn’t true of HyperCard clones today, and outside of our own little clique, barely anyone even knows of their existence.

(xTalk, Bettencourt)

LiveCode originally had an open source version, but it was discontinued in 2021. But LiveCode hasn’t had the same impact as HyperCard, for several reasons:

- As Atkinson said about SuperCard: “but it’s not like having it in the box” (Legacy 46:33). So people would need to know to download its open source version to use it.

- It builds compiled apps. This means that users can’t tweak and modify them, they can’t inspect them to see how they’re written, and they don’t even automatically see that they can build software using LiveCode.